New Scientist, 2nd July 2021

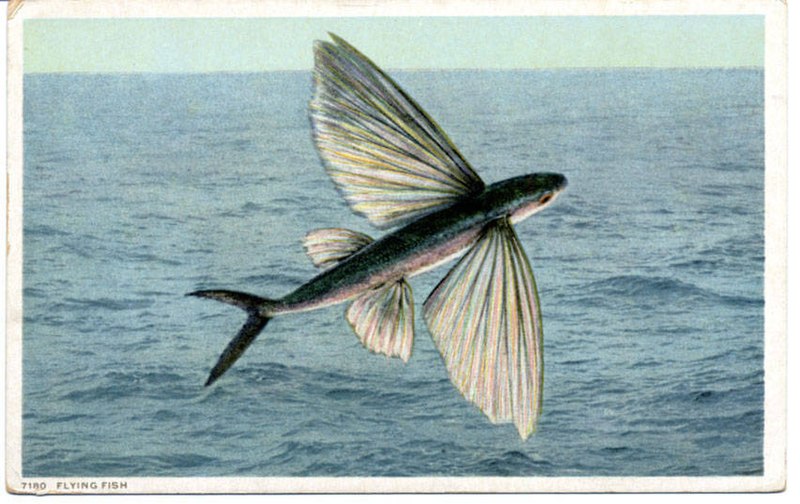

A pet fish adorned with tooth-like scales is helping biologists tackle a longstanding debate about the origin of teeth, and explore how body structures can be lost and regained during evolution.

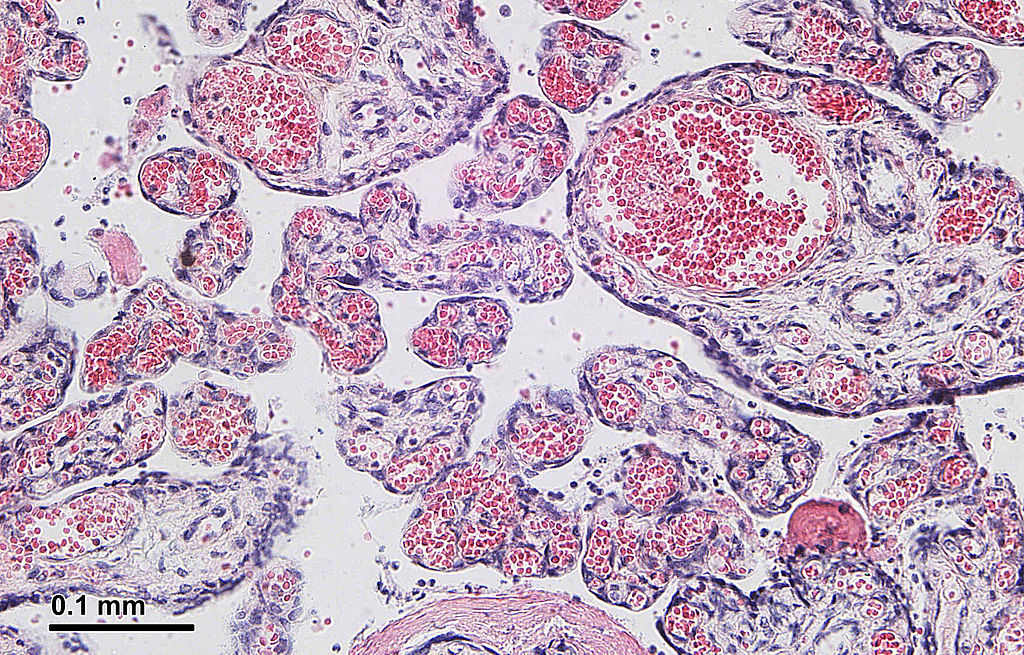

The suckermouth armoured catfish is commonly found in pet shops and, unusually for a bony fish, has tooth-like structures called odontodes covering its skin. These physically resemble teeth, erupting from thickened patches of skin to form layered structures of pulp, dentine and enamel, and similar genes appear to be active in both during development. But which evolved first, and how did tissues gain or regain them?

Their evolutionary history is complicated, because while ancient fish had similar structures, they were lost in most bony fish, but retained in fish with cartilage-based skeletons, like sharks. They re-emerged again independently in four different bony fish groups, including armoured catfish.

To find out more, biologists needed the ability to study and manipulate genes in a fish with skin odontodes, but zebrafish, a common model animal for these kinds of experiments, don’t have them.

Now Shunsuke Mori and Tetsuya Nakamura at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, have analysed gene activity in developing suckermouth armoured catfish skin odontodes. They uncovered a network of genes very similar to those found in developing teeth. “Most of the genes are shared,” says Nakamura.

One of these genes, pitx2, is needed for the first steps of tooth development, yet is absent from the skin odontodes of sharks. So Mori and Nakamura used gene silencing techniques to reduce the activity of pitx2 in the catfish and found that the odontodes didn’t develop properly…