Rare diseases band together toward change in research

Patients with rare diseases, and the scientists who study those diseases, were long inhibited by geographic sparsity. But the social-media age has made it much easier for them to band together to leverage their experience and push forward change.

Nature Medicine, 7th October 2020

“There were 150 people in one room at the same time suddenly being able to share. And that was so powerful.” Jillian Hastings Ward recalls attending the first conference, in September 2019, involving scientists, clinicians and the parents of children with a group of rare genetic neurological conditions called ‘GRIN disorders’. There are probably just a few hundred people in total worldwide with GRIN disorders, which means research into their conditions is scarce and there is no cure.

The conference is part of a drive involving the CureGRIN Foundation, a GRIN patient advocacy and patient-led research network, that aims to change that. For Hastings Ward, who is a member of CureGRIN’s board and whose six-year-old son Sam has a GRIN disorder, it felt like a real turning point. “It was really moving to see that many people get together, and the energy it generated in the room was fantastic,” she says. “That ability that we have to help them prioritise, do further research, is something that I’m quite hopeful about in the future.”

This idea of patients coordinating and driving the direction and pace of research is the raison d’être of a growing rare-disease patient movement that aims to transform the relationships among patients, scientists, clinicians and the pharmaceutical industry and thus bring treatments to the clinic much faster than would otherwise be possible.

Patients and their families are forming communities that go beyond patient support and advocacy, and they are actively networking scientists and clinicians together, building medical registries, deciding on research priorities, identifying scientists to work on these priorities and raising funds to support them.

This emerging role of patients as builders of new research-enabling infrastructures represents a shift away from the traditional narrative, in which patients are simply recipients of the fruits of medical research, toward one in which they are active, equal partners in its coordination, design and execution…

Read more: Nature Medicine 07 October 2020: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-1098-7

Image: Pixabay

Sex redefined

The idea of two sexes is simplistic. Biologists now think there is a wider spectrum than that.

Nature, 18th February 2015

As a clinical geneticist, Paul James is accustomed to discussing some of the most delicate issues with his patients. But in early 2010, he found himself having a particularly awkward conversation about sex.

A 46-year-old pregnant woman had visited his clinic at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Australia to hear the results of an amniocentesis test to screen her baby’s chromosomes for abnormalities. The baby was fine — but follow-up tests had revealed something astonishing about the mother. Her body was built of cells from two individuals, probably from twin embryos that had merged in her own mother’s womb. And there was more. One set of cells carried two X chromosomes, the complement that typically makes a person female; the other had an X and a Y. Halfway through her fifth decade and pregnant with her third child, the woman learned for the first time that a large part of her body was chromosomally male. “That’s kind of science-fiction material for someone who just came in for an amniocentesis,” says James.

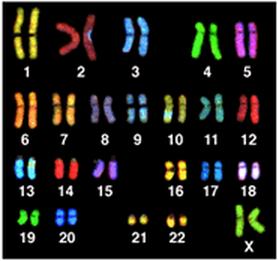

Sex can be much more complicated than it at first seems. According to the simple scenario, the presence or absence of a Y chromosome is what counts: with it, you are male, and without it, you are female. But doctors have long known that some people straddle the boundary — their sex chromosomes say one thing, but their gonads (ovaries or testes) or sexual anatomy say another. Parents of children with these kinds of conditions — known as intersex conditions, or differences or disorders of sex development (DSDs) — often face difficult decisions about whether to bring up their child as a boy or a girl. Some researchers now say that as many as 1 person in 100 has some form of DSD.

When genetics is taken into consideration, the boundary between the sexes becomes even blurrier. Scientists have identified many of the genes involved in the main forms of DSD, and have uncovered variations in these genes that have subtle effects on a person’s anatomical or physiological sex. What’s more, new technologies in DNA sequencing and cell biology are revealing that almost everyone is, to varying degrees, a patchwork of genetically distinct cells, some with a sex that might not match that of the rest of their body. Some studies even suggest that the sex of each cell drives its behaviour, through a complicated network of molecular interactions…