Deep and crisp and living: How snow sustains amazing hidden life

Snow may look pristine but even the freshly fallen variety is teeming with microscopic life. This vast and mysterious ecosystem could have a big impact on Earth

New Scientist, 18th December 2019

SHAWN BROWN’S field trip got off to a bad start when he discovered that his experiment had disappeared. He had travelled thousands of kilometres from the University of Memphis to Finland to study blood-red snow algae when a heatwave had turned his plans to mush. The sun had melted the dark red living patches, and now only white snow remained.

With funders to satisfy, Brown and his team struck on a Plan B: look for algae in the pristine white snow. They didn’t expect to find much, but to their surprise they discovered a rich hidden ecosystem of algae, fungi and bacteria. “I was just blown away by the biodiversity,” says Brown.

Until recently, microbes in snow were assumed to be rare and largely inactive. It is only in the past couple of years that scientists, including Brown, have used state-of-the-art DNA sequencing technology to reveal the secret life hidden there. As we learn more, it is becoming apparent that this is no mere curiosity: snow microbes play a role in cycling nutrients and carbon. They may be tiny but, given that snow covers a third of land on Earth, they could have an overlooked impact on the planet’s health and climate.

It may seem improbable that life could survive among ice crystals, given its dependence on liquid water, but microbes have evolved ingenious ways of eking out a living in snow. They grow in watery veins that run through the snow pack, melted either by impurities or by proteins that the microbes make. In extremely cold environments, some microbes slow their metabolisms to such a crawl …

Read more: New Scientist: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg24432611-100-deep-and-crisp-and-living-how-snow-sustains-amazing-hidden-life/

Image: Pixabay

Systems ecology: Biology on the high seas

How Eric Karsenti’s quest to understand the cell launched a trip around the world

Nature, 4th September 2013

It is 3 a.m. in mid-December 2010, an hour before dawn, and Tara is anchored amid an angry swell near the entrance to the Strait of Magellan. In the lee of Argentina’s cliffs, the 36-metre schooner and her crew have sought haven against the impending weather that has earned these latitudes the nickname the Furious Fifties. But as the winds gather to hurricane force, they snap the safety cord that eases tension on the anchor chain. As the crew struggles to replace it, the storm crescendoes, plucking Tara‘s anchor from the seabed twice before it can be secured again.

Bracing himself inside the aluminium hull is Eric Karsenti. Compact and bright-eyed beneath a bushy mop of white hair, he has the air of a seasoned seafarer. But he is also an accomplished molecular cell biologist who has spent most of his career studying microtubules — rod-like structures that form part of the cell’s internal scaffolding. Approaching retirement, he has switched fields, borrowed a famous fashion designer’s yacht and launched a 2.5-year expedition around the world to survey ocean ecosystems in unprecedented breadth and detail. Motivated by a love of adventure as much as by science, Karsenti has found his share of both…

Global ocean trawl reveals plethora of new lifeforms

Three-year Tara Oceans project publishes first analyses of rich diversity of planktonic life.

Nature, 21st May 2015

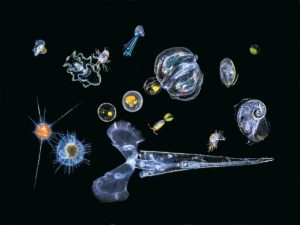

A team of researchers who spent three and a half years on a schooner fishing for microscopic creatures in the world’s oceans have reported the initial results of their survey — revealing a rich, diverse array of planktonic life.

Part scientific expedition, part adventure and part public-outreach effort, the project took place aboard the 36-metre Tara, which set sail from Lorient, France, in September 2009. Scientists onboard collected some 35,000 samples at 210 stations over the voyage, in a bid to build up a holistic view of Earth’s upper oceans.

The haul, details of which are analysed in five papers published today in the journal Science, includes a catalogue of more than 40 million microbial genes — most of which were not previously known — as well as some 5,000 genetic types of virus, and an estimated 150,000 kinds of eukaryote (complex cells), many more than the 11,000 types of marine eukaryotic plankton already known…